What Is the Ecological Footprint?

The ecological footprint is a measure of the biologically productive land and water area a population requires to produce the resources it consumes and to absorb its waste, using prevailing technology. In simple terms, it quantifies how much of the Earth’s “ecological budget” we use.

- Origin of the concept: Developed in the early 1990s by Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees at the University of British Columbia, the ecological footprint quickly became a central indicator of environmental sustainability.

- Difference from other indicators: Unlike the carbon footprint (focused only on greenhouse gas emissions) or the water footprint (focused on freshwater use), the ecological footprint is holistic. It integrates energy, food, housing, transport, and resource consumption into a single framework.

The ecological footprint is typically expressed in global hectares (gha)—a standardized unit representing the average productivity of all biologically productive land and sea on Earth.

History and Evolution of the Concept

- 1990s – Academic origins: The ecological footprint emerged as a way to visualize humanity’s demand on natural systems.

- 2000s – Policy adoption: Governments and NGOs began to use it in sustainability reports. Organizations like the Global Footprint Network institutionalized and standardized the methodology.

- 2010s – Awareness campaigns: Terms like Earth Overshoot Day—the date each year when humanity’s demand exceeds the planet’s annual biocapacity—gained media attention worldwide.

- Today: The ecological footprint is integrated into UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), corporate ESG frameworks, and educational curricula.

This evolution reflects its dual role: both as a scientific metric and as a communication tool to raise awareness about unsustainable consumption.

How Is the Ecological Footprint Measured?

Methodology Basics

The ecological footprint is calculated by tracking:

- Resource consumption: food, fiber, timber, energy.

- Waste generation: especially CO₂ emissions.

- Biocapacity: the Earth’s ability to regenerate resources and absorb waste.

The result is expressed in global hectares per person. If a population’s footprint exceeds its biocapacity, it runs an ecological deficit.

Biocapacity vs. Ecological Deficit

- Biocapacity: Earth’s capacity to regenerate resources in one year.

- Ecological deficit: When demand exceeds supply, leading to deforestation, overfishing, soil erosion, and climate change.

Limitations and Criticisms

- Oversimplification: Critics argue that reducing complex ecological processes to a single number may ignore local variations.

- Static assumptions: Technology changes, efficiency gains, and cultural behaviors may not be fully reflected.

- Still, despite limitations, it remains one of the most communicable and practical tools for sustainability.

Factors Determining the Ecological Footprint

- Energy consumption: Fossil fuel dependence is the largest driver, increasing CO₂ emissions and land requirements for absorption.

- Food production and diet: Meat-heavy diets require more land, water, and energy compared to plant-based diets.

- Transportation and mobility: Car use, aviation, and freight transport heavily increase national footprints.

- Urbanization and land use: Cities demand huge ecological support systems, including imported resources.

- Consumer behavior: Fast fashion, electronics, and throwaway culture amplify ecological stress.

Ecological Footprint by Regions and Countries

- United States: Among the highest per capita footprints, primarily due to energy-intensive lifestyles and transportation.

- China: Largest total footprint globally, driven by industrial production and rapid urbanization.

- European Union: Moderate to high per capita footprint; leading in renewable energy policies but high in consumption.

- Latin America and Africa: Lower per capita footprints but vulnerable to resource extraction and ecological degradation.

These variations highlight inequality in ecological responsibility: wealthier nations tend to consume disproportionately more resources.

Global Impact of the Ecological Footprint

- Climate change: Oversized ecological footprints accelerate greenhouse gas emissions.

- Biodiversity loss: Deforestation, land-use change, and overfishing reduce ecosystems’ resilience.

- Water scarcity: Excessive agricultural and industrial demand contributes to global water crises.

- Resource depletion: From rare earth metals to fertile soils, humanity is drawing down nature’s capital at unsustainable rates.

Reducing the Ecological Footprint

Individual Actions

- Adopt plant-rich diets and reduce food waste.

- Prioritize public transport, cycling, and electric mobility.

- Shift to renewable energy sources at home.

- Consume less, buy durable goods, and recycle.

Business Strategies

- Implement circular economy models.

- Measure and report ecological footprints alongside carbon footprints.

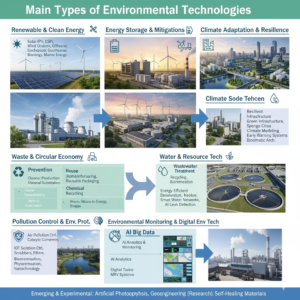

- Adopt renewable energy and efficiency technologies.

Policy and Governance

- Carbon pricing and emissions reduction commitments.

- Sustainable urban planning and green infrastructure.

- International treaties like the Paris Agreement.

Criticisms and Alternatives

While the ecological footprint is influential, critics argue for complementary tools:

- Water footprint: essential for agriculture and drought-prone regions.

- Carbon footprint: more precise for climate policies.

- Planetary boundaries framework: integrates multiple Earth system thresholds.

Still, the ecological footprint remains the most communicative “umbrella” metric for sustainability.

The Future of the Ecological Footprint

- Technological innovation: AI, renewable energy, precision agriculture can reduce global pressure.

- Cultural shifts: Younger generations driving minimalist and eco-conscious lifestyles.

- Education: Ecological literacy integrated into school systems worldwide.

- Policy evolution: Stronger integration into SDG monitoring and corporate ESG accountability.

Toward a Sustainable Planet

The ecological footprint is more than just a metric it is a mirror reflecting the unsustainable patterns of modern civilization. While criticisms exist, its strength lies in its ability to make global sustainability challenges understandable and actionable.

If humanity can reduce its footprint and live within the planet’s biocapacity, it will secure a future that is not only ecologically viable but also socially just. The ecological footprint reminds us that every choice matters, from what we eat to how we power our homes and how we move across cities.