What Are Ecological Corridors?

An ecological corridor also referred to as a biological corridor, green corridor, or ecological connectivity pathway is a designated area of land or water that links two or more natural habitats. Its primary function is to maintain ecological connectivity, enabling the movement of species and the flow of natural processes such as migration, seed dispersal, pollination, and genetic exchange.

Ecological corridors are not limited to long, continuous strips of vegetation. They can include riverbanks, wetland networks, scattered forest patches, agroecological landscapes or large scale protected area systems that operate collectively as a connectivity network.

Types of Ecological Corridors

Linear corridors

Continuous natural elements such as riversides, hedgerows, riparian forests or forested strips that provide direct pathways for wildlife movement.

Discontinuous corridors

A sequence of small habitat patches spaced closely enough to allow species to move between them in short jumps.

Landscape mosaic corridors

Extensive ecological networks made up of protected areas, buffer zones, restored ecosystems and sustainable land use areas that operate as a multi scale connectivity system.

Why Ecological Connectivity Matters

Genetic Flow, Species Movement and Ecosystem Resilience

Connectivity supports gene flow among isolated populations, reducing inbreeding risk and increasing longterm species viability.

Improved Ecosystem Resilience

Connected ecosystems are better able to adapt to disturbances such as fires, droughts, climate shifts and human pressures, ensuring long term ecological stability.

Preventing Habitat Isolation

Ecological corridors counteract the impacts of landscape fragmentation by enabling animals, plants and other organisms to move freely across otherwise disconnected habitats..

Global Examples of Ecological Corridors

Ecological corridors exist on every continent, ranging from small wildlife crossings to continental networks spanning thousands of kilometers.

Continental-Scale Corridors

Yellowstone Yukon (Y2Y) North America

Extending roughly 3,400 km across the Rocky Mountains, this corridor allows grizzly bears, cougars, wolves, caribou, and lynx to move freely. As I often highlight when studying large scale connectivity, Y2Y demonstrates how linking protected areas increases ecosystem resilience under climate pressures.

Mesoamerican Biological Corridor

Stretching from southern Mexico to Panama, this corridor protects 7–10% of the world’s known species. It connects tropical forests, wetlands, and protected parks, enabling the movement of pumas, tapirs, monkeys, and migratory birds.

Jaguar Rivers Initiative – South America

A continental scale corridor (~2.6 million km²) reconnecting river systems and forests across Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia. Its purpose is restoring jaguar populations, aquatic mammals, and wetland ecosystems. When studying its approach, I noticed the innovative use of river networks as “natural ecological highways”.

Regional and National Initiatives

European Green Belt

Over 12,500 km along the former Iron Curtain, linking mature forests, riparian valleys, and mountain habitats. This is Europe’s longest ecological corridor and a sanctuary for bears, lynx, and rare birds.

Mata Atlântica Central Corridor – Brazil

Connecting fragments of the Atlantic Forest in Bahia and Espírito Santo, protecting specie rich tropical habitats and restoring highly fragmented biomes.

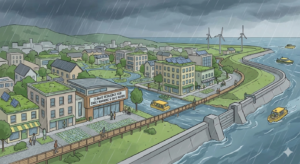

Urban Ecological Corridors

Cities like Beijing, Vitoria Gasteiz (Spain), Bogotá (Colombia), and Quito (Ecuador) are building urban green corridors that connect parks, riversides, and green belts. In my experience, these projects not only support birds and pollinators but also reduce heat islands, increase air quality, and offer recreational benefits to millions of people.

Benefits: Biodiversity, Climate and Ecosystem Services

Biodiversity Recovery

- Enhances movement and migration

- Supports recolonisation of degraded sites

- Maintains genetic diversity

- Increases long term population viability

Climate Adaptation & Carbon Capture

- Enables altitudinal and latitudinal shifts

- Connects climate refugia

- Strengthens carbon sinks across restored and forested corridors

Ecosystem Services

Healthy corridors provide:

- pollination

- pest control

- water filtration

- flood reduction

- soil stabilization

- urban cooling

These services have measurable economic value, making ecological corridors a nature based solution with broad social benefits.

Ecological Corridors in Urban and Regional Planning

Green Infrastructure Design

Corridors are integrated into modern planning frameworks as part of nature based solutions, combining urban parks, reforested riverbanks, peri urban forests and connected natural areas.

Land Use Planning

Many countries now mandate ecological connectivity in territorial planning:

- zoning rules

- ecological buffers

- wildlife crossings on highways

- restoration of riparian vegetation

During my own work with land use plans, I’ve seen how specifying minimum widths, vegetation types, and management rules dramatically improves corridor functionality.

Community and Municipal Initiatives

From indigenous led conservation coalitions to local governments installing vegetated overpasses, corridor planning is increasingly participatory and multi sectoral.

Legal and Policy Frameworks

International Conventions

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity): Emphasizes ecosystem connectivity in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

- CMS (Convention on Migratory Species): Prioritizes migratory routes and ecological networks.

- IPBES: Highlights connectivity in its rapid assessments.

National Legislation

- Brazil: SNUC law formally defines and regulates ecological corridors.

- Canada: National definition: “an area of land and water that maintains or restores ecological connectivity.”

- EU: Biodiversity Strategy 2030 requires restoring ecological coherence across member states.

- Puerto Rico: The 2013 law declared the Northeast Ecological Corridor a protected reserve.

Local Policies

Municipalities adopt green belts, minimum green infrastructure standards, and biodiversity master plans to reintroduce nature into built environments.

Challenges and Opportunities

Challenges

- Limited land availability

- Conflicts with agriculture and real estate

- Risk of spreading invasive species

- High costs of land acquisition and monitoring

- Complex scientific modeling of species movement

Opportunities

- Nature based tourism

- Carbon credits and green investment

- Jobs in restoration and ecological monitoring

- Large scale landscape recovery

- Climate resilience and disaster risk reduction

Corridors transform fragmented ecosystems into living, resilient networks unlocking environmental and economic benefits simultaneously.

How to Design Effective Ecological Corridors

Design Principles

- Ensure minimum width and habitat quality

- Prioritize native vegetation and riparian buffers

- Connect protected areas and high biodiversity landscapes

- Reduce barriers (roads, urban barriers, fences)

- Integrate wildlife crossings where needed

Monitoring and Adaptive Management

Corridors evolve. Species tracking, camera traps, satellite imagery, and ecological indicators help adapt their design over time. From what I’ve seen, adaptive management is the single most important factor separating successful corridors from those that fail to maintain real connectivity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main purpose of an ecological corridor?

To maintain ecological connectivity, allowing species and natural processes to move freely.

Do ecological corridors work in cities?

Yes. Urban green corridors reduce heat, improve air quality, and support pollinators and birds.

Are corridors expensive to build?

Costs vary, but their long term benefits in biodiversity, climate resilience and ecosystem services often outweigh the investment.

Can corridors reduce species extinction?

Absolutely. By reconnecting fragmented habitats, they restore gene flow and population viability.